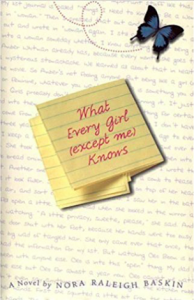

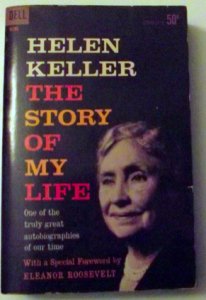

In 2001, after the publication of What Every Girl (except me) Knows, I returned to New Paltz Middle School to speak to the sixth-grade students. I was, after all, a sort of hometown success story, right? My first stop was the library upstairs. I wanted to share with the librarian how important books had been to me when I was in this very building, in particular The Story of My Life by Helen Keller.

Living in a world of darkness and silence, with no ability to be heard and no understanding of how to be seen without acting out—by all accounts Helen Keller could throw a wicked tantrum—her story was as familiar to me as my own. I understood why you would fling a fork across the room if you had no other means of communicating. I knew what that kind of anger felt like.

I was neither blind nor deaf, but the lies I had been told about my mother’s suicide when I was three and the subsequent living arrangements made for me with adults who were not my family —and who were, to put it mildly, not very nice— had left me in my own darkness of confusion, fear, and loneliness.

Enter Helen Keller.

I stumbled upon her book during a weekly trip to the middle school library where we students were left to roam free! Choose whatever we wanted! All we had to do was fill out the little card in the back of the book with our name, then stand in line so the librarian could stamp the card with a return date, ensuring we would bring it back.

Maybe I picked this little book because it was so small and compact and cute. Maybe I liked the red cover with the smiling old lady peering out from an all-black background. Maybe I was drawn to the simple title: The Story of MyLife. Most likely, I simply

recognized the name of the famous woman who had written the foreword. Not that I had any idea what a “foreword”was, but I had been cast as Eleanor Roosevelt in a classroom play the year before. In any event, I took the book home, read it, and I fell in love.

Helen was feisty. And angry. She was a fighter. She didn’t give in and she didn’t give up. She got in lots of trouble as a kid. She was scared. Confused. And strong. She was smart, and she was a real person.

Then, look what happened when Helen Keller connected language to the human emotions raging war in her mind. Look what happened when she learned how to read, to speak, to be heard—without hitting, wailing, and flailing about. Helen Keller grew up, and more than surviving, she succeeded. She thrived. She went to college—to Radcliffe, for goodness sakes! She had something to say and she found a way to say it. She “spoke” and people listened.

If Helen Keller could have a miracle, couldn’t I?

Then, one crystal clear sunny winter day, my sixth-grade language arts teacher announced that, before he handed back last week’s homework assignment—which had been to write a story—he was going to read the best one out loud.

My miracle.

Because only a few months after being unceremoniously returned to my father, and only a month after being suspended from sixth grade—did I mention I was angry and acted out a lot?—Mr. Thomsen saved my life. Without knowing it, he showed me a way to exist, a way to be seen and heard that didn’t involve shoplifting or smoking cigarettes on the middle school track.

In short, Mr. Thomsen was my Annie Sullivan. I didn’t make the connection at the time I was reading The Story of My Life by Helen Keller, I just knew I didn’t want to return this book to the library. I needed to own it.

I had to have this book in my bedroom, in my possession, close by, like a promise that no one could take away from me. And apparently, during those middle school years, I also needed to have Cleopatra of Egypt. A Wrinkle in Time. Black Beauty. Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and Me, Elizabeth. And a few particularly good Nancy Drews.

Back to 2001—

“I think, I can tell you something funny now,” I said to the librarian. We were alone in her small office behind the circulation desk. I couldn’t be sure that she wasn’t

the same woman who had been there twenty-five years earlier. She looked pretty old to me, but she quickly corrected me: No, she had not been working here in 1973.

“Well, when I really loved a book,” I went on, “I just used to take it. I wanted it so badly.”

She looked at me blankly.

Surely, she’d get what I was saying. I just needed to explain it better. Wasn’t I here as a published author? Don’t all authors have some quirky story about their special relationship with the library?

“You what?” she asked.

“I’d steal them,” I laughed. “You know, because they were so special to me. I wanted to keep them.”

She wasn’t laughing.

Actually, I make this very same incorrect assumption fairly often; I believe that somehow people know me, as if somehow my whole history is written on my face, as

if it must be so obvious that I was left alone when I was really little, and surely anyone could understand my need to grab what I could, take what I needed because if I didn’t no one was going to do it for me. How could I have survived without these stories?

“You have library books?” she asked me. “That you didn’t return? How many?”

I was starting to get nervous. This wasn’t going well at all. I could see her calculating the late fees in her head. Oh, boy what did she think? That I was that stupid? That I’d check the book out in my name and just not return it?

“Oh, no,” I said, assuring her. “I wouldn’t sign them out, but if it was a book I really loved, and I just needed to own it, I would return it on time, then come back later and just take it.”

This didn’t seem to help much.I considered showing her how I would lay the precious book against my chest, hidden by my spiral notebooks and binder. Or how I would slip it under my sweater and walk oddly upright past the circulation desk, my heart pounding with fear. Maybe if I just explained that I loved those books so much that I still own them. They sit on my shelf, next to the hundreds of other books I’ve since purchased, but in their own very significant spot.

If I could just get her to understand.

Instead, I stood up. I was due back downstairs to give my author talk to the sixth graders in a few minutes. I had been told Mr. Thomsen was going to show up. And after all these years, I wanted to tell him my story: The story of my life.

I knew he had no idea what he had done for me. He had no idea that I had been standing at a crossroads as a twelve-year-old in 1973 and that it had been he who offered me an identity other than “troublemaker.” That if it hadn’t been for him I wouldn’t be here now, a published author, speaking to children, telling them they too have a voice worth being heard.

It was time to pay it forward.

“I needed to have books,” I told the librarian.

I needed those stories.

Originally published

NCTE Voices From the Middle

Vol. 24, Issue 4, May 2017

Cleopatra of Egypt byLeonora Hornblow, World Landmark Books W-50. First published Random House, 1961.

Black Beauty by Anna Seward. First published F. M. Lupton Publishing Company, 1877.

Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and Me, Elizabeth by E. L. Konigsburg. First published Antheneum Books, 1967.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeline L’Engle. First published Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1962.

The Story of My Life with Special Foreword by Eleanor Roosevelt by Helen Keller. Dell, 1961.