Disappointment or Love? Just Love

By Meira Rosenberg

It’s a funny thing, disappointment. I think it must be the first cousin of regret, noodling around together in our subconscious with evil half-smiles on their faces poking at this memory and that until they hear an ouch.

Every now and then, or maybe every day, I wonder if my parents would be disappointed in me. On bad days, I think yes—deeply. But to put it out there at the outset, this is all me.

My mother, who died suddenly nearly thirty years ago, was clear in her not-disappointment. Because she died without warning, my father and I were—once our explosive grief allowed—we were even more careful than before to talk and talk, to ask and answer.

My father, too, was clear in his not-disappointment. He and my mother enveloped me with love. The real kind. The kind that made me feel safe and warm, the kind that was smart and funny and all the good stuff, but let me know when I’d done something wrong or said something hurtful, without being hurtful in the letting me know.

What is all this, then?

My love for my parents didn’t vanish when they died, but I was disappointed in myself that I couldn’t save them, that I couldn’t will away the cancer or turn back the disease. I was disappointed that my mother never knew our youngest son, and died when our older two children were babies. Disappointed that though my father knew our children so much better, it was for far too short a time.

And disappointed that my parents did not live long enough to become a burden, a burden that I had longed for, because it would have meant that they had grown very old.

I remember the good things, and far more often. But these, I think, are the disappointments worth wallowing in now and then. Not the ones that poke and prod to make us feel badly about ourselves, but the disappointments that, muddled together with regret and grief and longing, grow from love.

Omens

By Dave Donelson

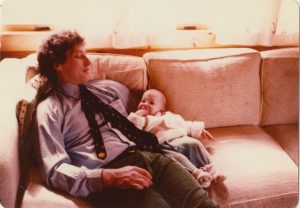

Can the birth of a beautiful baby girl be a disappointment? I’ll let you decide. At the time our daughter, Leigh Anna, was born, many, many emotions ran through us and I suppose disappointment may have been one of them, but if it was, it was the least of our feelings.

There seemed to be omens about her birth that started in Acapulco. Eileen was showing but not hugely pregnant when we went. I was working, leading a group of advertisers who had won the trip by spending copious amounts of money on the television station where I worked. The first incident that should have sent alarm bells ringing was a joke one of the tour guides told to our bus when Eileen boarded.

He noticed her condition, asked if this was her first baby, then, without waiting for an answer, asked if she’d like to know how childbirth felt. Again, she didn’t have a chance to answer before he said, “Take your upper lip in your finger and thumb and squeeze it. Not too bad, huh? Now, pull it over the top of your head.” Ha Ha Ha. Crude and not appreciated by either one of us. But what could we do?

Then there was the book I took along with me, Joseph Heller’s “Something Happened,” one of the most depressing novels I’ve ever picked up. Read on top of several margueritas, it did not stimulate a positive outlook toward parenthood.

When we returned to the states, Eileen’’s physical troubles with the pregnancy began and she spent most of the time until the birth in bed. It was a difficult delivery, taking hours and involving infections and other unfortunate complications. When Leigh Anna was finally born, the doctor greeted me not with congratulations, but with the opinion that the baby should be institutionalized before Eileen came out of the anesthesia.

“She’s mongoloid,” he said.

Cold Feet

by Piper Goodeve

My memories from around the time of my father’s death will haunt me until I too pass on. I feel this to be true, despite what people say. “Oh, it will get easier.” “Oh, it won’t hurt so much in a few years.” “Oh, you’ll start to remember the good times, not just the bad.”

Will I? Two years in and I am not so sure.

What haunts me is not how we fought (which we did), and not what I did for him (which was not enough), but how disappointed he was in himself.

I rubbed his feet, bony and chilly even through the thick socks he wore in the summer, the chemo making him continually cold.

“Oh, that feels nice,” he said. And then he started to cry.

“Dad, what’s the matter?” I pulled my hands back thinking I had inadvertently hurt him. When he could catch his breath, I heard, weakly, “I squandered so much.” It broke my heart. No one wants to see their parent this way.

My father was raised in Connecticut, prepped at Deerfield, was a legacy kid at Yale, but didn’t go. He studied film making at BU instead, but dropped out in his junior year. He became a mechanic, fixing Volvos in Boston, and smoking and drinking and listening to Bob Dylan with my mom at bars in Somerville. When I was born he needed a “real job,” so he became an accountant. Quite a difference from someone who wanted to make movies. Quite a difference from wearing jeans covered in motor oil and cigarette burns. Now he crunched numbers and wore a tie. Throughout my life with him, a too-short forty years, I saw him as a happy and content man. And to learn on his bed one summer day in New Hampshire, on his death bed, literally, that this was not the case, was crushing.

“Dad, you’ve had a wonderful life,” I choked out. “It’s ok.”

He rolled the side of his face into the cream-colored pillow and let out a breath. “I wanted to be a writer,” he whispered.

Heartbroken, I went back to rubbing his feet.

Piper Goodeve is an actress originally from New Hampshire, whose love of books and telling stories led her to a career in audiobook narration. She is now an Audie Award and Earphones Award winning narrator, and has narrated over 250 audiobooks. She splits her time between Brooklyn and Vermont with her husband and their rotund cat, Caroline. www.pipergoodeve.com

Piper Goodeve is an actress originally from New Hampshire, whose love of books and telling stories led her to a career in audiobook narration. She is now an Audie Award and Earphones Award winning narrator, and has narrated over 250 audiobooks. She splits her time between Brooklyn and Vermont with her husband and their rotund cat, Caroline. www.pipergoodeve.com

Meira Rosenberg

Meira Rosenberg writes middle grade novels as well as essays (especially in Nora’s workshop these days) and short stories. She is also working on a novel that so far is shaping up to be for adults. She lives in Connecticut with her husband and their rascal of a puppy, but their three children have flown the coop. To learn more about Meira and Indiana Bamboo, visit www.MeiraRosenberg.com

Dave Donelson is a freelance journalist with a dozen books of fiction, non-fiction, memoir, and poetry to his credit. His most recent work is The Journal of My Seventieth Year. www.davedonelson.com.

Gae

March 12, 2022 - 5:44 pm ·These are beautiful and heartbreaking.